Church members with long giving histories are increasingly retiring to fixed incomes, and younger givers aren’t yet picking up the slack. This socioeconomic dynamic and many others related to living in a modern and mobile society are affecting every church’s financial bottom line. In order to cultivate future donors and better understand their current donor base, more and more church leaders are collecting donor data and poring over the numbers. But it takes skill and ingenuity to analyze the data correctly and to properly weigh important indicators of long-term financial health and of looming obstacles.

“I think there’s a lot of room for improvement,” said CPA Vonna Laue, a senior editorial advisor for Church Law & Tax. “You can have a lot of data, but if you don’t know how to use it, it doesn’t help much.”

A culture change is also necessary, stressed Randy Ongie, president of MAG Bookkeeping in Cumming, Georgia, and former executive pastor at Grace Fellowship Church in Johnson City, Tennessee. “Church leaders were accustomed to not having to cultivate giving. It was not part of the needed training,” Ongie said. “Now they do.”

Data put to good use

Atlanta’s 12Stone Church is a congregation that has a pretty good handle on both collecting data and putting it to good use.

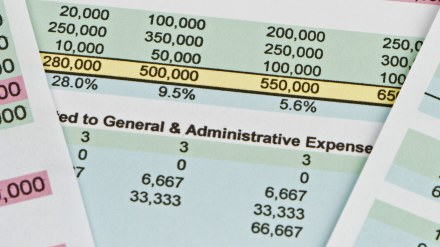

As the church’s chief financial officer, Norwood Davis joined the staff in 2005 and was ready to put into practice his extensive experiences in the business world—including collecting and analyzing data. The church already had plenty of data to analyze. Even before Davis came on staff, 12Stone had been collecting financial and demographic information on spreadsheets for around six years. Still, little had been done with all those facts and stats. This was about to change. With plans to move from a single congregation to a multicampus church, 12Stone needed a financial model to fit the multicampus concept. Davis was more than ready to dig in to see where the data led.

Davis became especially interested in data that explored five levels of engagement: (1) giving, (2) serving, (3) small-group participation, (4) whether attendees had kids involved in the church’s children or youth ministries, and (5) any kind of “affirmative engagement” with the church (filled out a prayer request or information form, attended a seminar, and so on). With 12Stone’s focus on building disciples—and since engagement is an indication of discipleship—this metric has helped 12Stone grow disciples. Obviously, there are financial implications to deeper engagement on all levels. “Engagement is a gateway to giving,” Davis said. “As people get more engaged, they become better givers.” For Davis, spiritual growth and tithing go hand in hand. This is true for baby boomers, millennials, and any other demographic group, Davis added.

Another key metric for 12Stone: giving per person per week. This metric focuses on collecting data on attendance and giving during the worship services. The giving-per-person-per-week data not only became useful in creating the financial models for a multicampus church but it continues to guide the church’s financial decisions.

In those early days of his research at 12Stone, Davis would plot the giving-per-person-per-week data on a simple X-Y graph. Specifically, he was looking at long-run averages compared to short-term moving averages. The results were, to say the least, fascinating. And instructive. The church’s short-term averages were running about 20 percent above the long-term averages. Davis also started seeing patterns related to specific seasons, holidays, and even weekends after common paydays.

Prior to Davis’s data study, the church could have easily overestimated revenue by focusing on the short-term spikes. But by looking at long-term averages, 12Stone was able to set a more realistic budget.

Giving units, debt, and attrition

When Ongie consults with church clients, he always tells them to think in terms of giving units—a variation on 12Stone’s approach. A family of four, for example, is a single giving unit, while a pair of roommates is two giving units. Ongie tells clients to track dollars donated per year per giving unit.

“I like to see it expressed that way,” he said. “That’s a different approach than just looking at an aggregated amount on your financial statement.”

If a church is in debt more than three times its annual giving, trouble may lurk down the road, and the church will have to continue to grow rapidly in order to stay sustainable, according to Ongie. Particularly if the debt is largely tied up in facilities, there’s also a danger of running out of space and having to incur more debt. “After a while, it’s chasing the train as it picks up speed,” he said. “You’re never going to catch it.”

Ongie also recommends that churches gauge their long-term financial health by paying attention to both the number of people regularly entering the system and to the rates of giving.

“Every church has a back door,” he said. People leave or move, and all sorts of things happen. If more than 4 or 5 percent of any given weekend’s visitors aren’t first- or second-time attendees, there’s a good chance the church has plateaued and may be starting to decline. “You’re going to have attrition,” Ongie said. “You’d better be attracting new people in.”

Greg Morris, chief opperating officer and cofounder of Elevate Group, an organization that equips church leader to call their people to great engagement and commitment.

“That always amazes me that churches have no idea who has stopped giving,” Morris said. “People don’t stop giving for no reason. Something has happened in their lives.” If someone stops giving, two weeks later, he or she might leave the church.

Among those who are giving, churches should analyze their giving units’ rates of giving within the context of average household income in their areas, according to Ongie.

“What kind of percentages of income do they give compared to potential?” he said. One church with which Ongie consulted had a rate of giving per unit of about 8.5 percent of income, so he cautioned the church that it appeared attendees were already giving at a high rate.

“I’d be careful not to keep banging on the same people’s doors for more money,” he told the church. “I would celebrate the fact that they already give at a high rate.” Instead, the church would need to grow by increasing its number of giving units. Typically, half of a church’s giving units don’t give. “The challenge is to grow the number of giving units,” he said.

CPA Laue also encourages churches to think in terms of giving units, and to pay attention to trends in their local communities, which they can glean from US Census Bureau data. She also advises churches to compare themselves to peers. For example, CapinCrouse’s Church Financial Help Index allows churches to compare their finances to other congregations. And if churches are part of a denomination, they can often get benchmarking data from their denomination.

Identify the data’s unique story

Churches should study annual giving trends within their own congregations and regularly monitor their debt, according to Laue. Even if a church appears to be growing, it should navigate that growth carefully. “A church can grow, and it takes a period of time between when they get new people attending church and when those people financially contribute to the church,” she said. There’s a danger of growing too quickly before contributions catch up.

There’s also the danger of rushed assumptions. “It’s so easy to grab onto one piece of information and say, ‘See? We’ve got an issue,'” Laue said.

One example of a potentially dangerous assumption: a business administrator might note that the church is only spending 40 percent of its budget on salary and benefits compared to other churches, which might spend 45 to 55 percent on those expenses, and automatically assume the church should give raises. Another example: a church’s finance committee might point to its spending 58 percent of the budget on staff as a sign it should immediately lay people off.

“There’s a story behind all of the numbers,” Laue said. Churches should consider what might be unique to their situations when they weigh their data. “Any of this information is a starting point,” she said. “It should start a dialogue.”

This article includes additional reporting by Matthew Branaugh, content editor, and Chris Lutes, web editor.